Excuses, excuses.

Excuses can be seen as a way to mitigate personal responsibility or as a subtle form of apology. We often use them in hopes of softening the frustration of someone we have let down, yet consistently relying on excuses can reveal a conscious or unconscious attempt to manipulate other people’s emotions, seeking either pity or control. It’s important to differentiate between someone making an excuse to spare another’s feelings and someone doing so to avoid accountability.

We employ all kinds of excuses to justify poor behaviour. These excuses spring from our belief system and are fertilised by unconscious guilt, shame or denial. Admitting we are wrong deflates the ego, while using an excuse neutralises the effect on our self-esteem. Using excuses like being distracted or overwhelmed with work is less damaging to our ego than admitting we are negligent or forgetful. Excusing our behaviour shifts responsibility to external factors, allowing us to avoid accountability. In so doing, we do not have to feel or process any guilt associated with our behaviour.

When we continually use excuses to mask our behaviour, we are signalling to the world that we have no control over our actions. Our energy conveys that we are not mature enough to take responsibility for our choices and their consequences. Excuses and denial are weeds that choke the seeds of potential. Every excuse we make to avoid facing our emotions stunts our growth, and the harm we inflict on our authentic self is mirrored back to us by the outer world.

Energy Signals

Feelings, such as shame and guilt, are less desirable than dignity or pride, and call for humility. It is the value judgment we attach to an emotion that characterises the feeling as right or wrong, good or bad. These labels are often subjective and are shaped by past experiences and beliefs. The key to releasing an emotion is to allow it to exist without assigning a value to it. This form of acceptance is transformational.

Emotions are energy signals from our body informing us of certain behaviours that are out of alignment with our authentic self. If we’ve wronged someone, they serve as a prompt to address the situation. If we avoid the prompt, the energy from the emotion is projected in the mind and becomes distorted by value judgements. For instance, a man cuts ahead of people queueing at a coffee takeout. He becomes aware of an energy signal that indicates he is out of sync with the people around him (our collective energy comes from the same source). Instead of apologising or stepping back in line, he ignores the emotion, and it triggers a feeling response such as ‘I’m justified because I am in a hurry’, or, ‘I am a regular customer and deserve to be served first’.

An objectified emotion becomes a feeling. Continuing to ignore energy signals lead to further projection of hurt and pain onto the world around us, which can manifest in disagreements at work, or arguments at home. If not addressed, these situations escalate into conflict and drama.

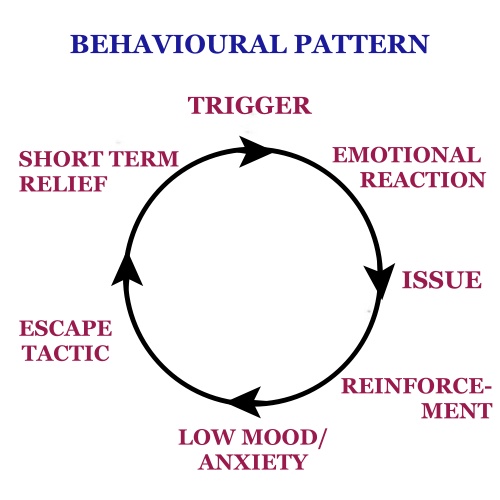

We may automatically use avoidance as the best option to numb our feelings by binging on TV, food or drink. Regardless of the avoidance strategy we use, we are letting our unresolved conflicts dictate our behaviour instead of confronting the issue. When we deny a feeling within us, we consign the energy to the unconscious where it causes behavioural defects. When we avoid necessary conversations to resolve conflicts, it often stems from a fear of the outcome. We may have witnessed or participated in conflicts that led to irreparable breakdowns, which have shaped our coping strategies. We might either avoid disputes altogether to preserve a relationship, or end a relationship to steer clear of conflict. This is the foundation of maladaptive behaviour, where we link every tense argument to a potentially explosive situation based on our history.

Releasing Emotions

We need intention and self-awareness to follow our behaviour back to its origin. We also require determination. We have magpie minds that alight on glitter rather than mining for real treasure. Once we recognise disturbing thoughts and behaviours, we may feel compelled to struggle against them. We falsely believe that by fighting them, we can eliminate unwanted inclinations. However, our role is simply to be an observer. When we observe difficult thoughts, we must also experience the emotions that accompany them. Avoiding our feelings can result in mental wrestling, leading to a chaotic spiral of thoughts. Notice an emotion in your body that is triggered by a thought or feeling. (Remember, a feeling is an emotion embellished with value judgements; an emotion is a sensation stripped of thought.) Allow the emotion to be as it is, whether it is a tingling or heavy sensation; just observe it without resistance or judgement. With this continued practice, the energy will release and it can no longer fuel difficult thoughts and maladaptive behaviour.

When we become aware of maladaptive behaviours and their source, they cease to have an unconscious hold over us. Instead of an automatic reactive response in a triggering situation, we have a conscious choice of how we act, or react to the emotional stressor. Avoidance is a maladaptive behavioural response to excessive fear and anxiety. Avoiding challenging situations may provide temporary relief, but it can hinder personal growth and fulfilment over time. Avoidance as a coping mechanism leads to dependence, and it undermines our confidence.

We must push through limiting attitudes if we are to germinate and grow. A seed needs darkness to germinate and light to grow. When we are immersed in darkness, we are in germination; we must keep pushing through until we reach the light of a new consciousness, a higher level of understanding. Life is cyclical, seasons come and go, and we are perennial, cosmic flowers having a human experience.

Taken from A Compass for Change

June 2025