Making Sense of Reactions That Once Kept You Safe

When someone has lived with emotional abuse, their reactions later in life can feel confusing or even frightening to them. They may feel overwhelmed by emotions, struggle to calm themselves, or wonder why certain interactions affect them so deeply. Often, what they are experiencing is emotional dysregulation, not because they are failing to cope, but because their nervous system learned to survive in an unsafe emotional environment. Emotional abuse doesn’t always look dramatic from the outside. It can be subtle, ongoing, and hard to name. It might involve criticism, emotional withdrawal, unpredictability, or being made to feel small or ‘too much.’ Over time, these experiences shape how a person relates not only to others, but to their own inner world.

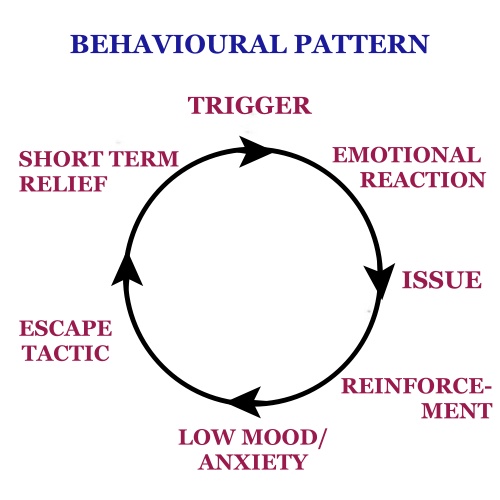

When emotions were not safe to express, or when love felt conditional, the nervous system adapted. It learned to stay alert, to watch for changes, to anticipate harm before it arrived. These adaptations were intelligent responses at the time. They helped the person remain connected, avoid rejection, or minimise emotional pain. The difficulty is that the nervous system doesn’t automatically update when circumstances change.

Body’s Response

Many people describe feeling as though their reactions are out of proportion to the present moment. A tone of voice, a silence, or a perceived shift in connection can bring a surge of fear, anger, or despair. Intellectually, they may know they are safe, yet emotionally they feel anything but. This isn’t a failure of insight or self-control. It’s the body responding to something that feels familiar, even if it no longer reflects the current reality.

When emotional abuse occurs within close relationships, particularly in childhood or long-term partnerships, attachment becomes intertwined with threat. The person they need for safety is also the person who causes pain. In these circumstances, the nervous system often chooses connection over protection. People learn to minimise their own needs, to take responsibility for others’ emotions, or to work harder to preserve closeness, even when it costs them.

Healing the Nervous System

Later in life, these patterns can reappear in adult relationships, especially during conflict, separation, or emotional distance. A sense of stability may feel fragile. Calm may feel temporary or unreliable. There can be a strong urge to repair, to fix, or to hold things together, alongside moments of emotional shutdown or exhaustion. Again, these are not signs of weakness. They are echoes of earlier survival strategies.

Healing emotional dysregulation is not about learning to control emotions or make them disappear. It’s about helping the nervous system experience safety in new ways. This is a gradual process. It involves becoming curious about bodily sensations, learning to recognise the early signs of overwhelm, and developing ways to settle the system rather than override it.

Just as importantly, healing often involves grief. Grief for the safety, consistency, or emotional calibration that was missing earlier in life. Allowing space for that grief can be deeply regulating in itself. Over time, as safety is built from the inside out, emotions become less frightening. They begin to move through rather than take over.

For those living with the effects of emotional abuse, it’s important to say this clearly: there is nothing inherently wrong with you. Your responses make sense when understood in the context of what you lived through. Healing is not about becoming someone different. It’s about slowly, compassionately helping your system learn that it no longer has to live in survival mode.

Change doesn’t come from self-criticism or pushing harder. It comes from understanding, from patience, and from relationships, including the therapeutic one, that offer steadiness where there was once uncertainty.

Collette O’Mahony (Dip.Psy.C) Psychotherapy

For a free 15 minute introduction, email me at: info@colletteomahony.com (include your name, email address and goals for therapy).